Baden-Baden: Summer Capital of the Belle Époque

Introduction and user guide:

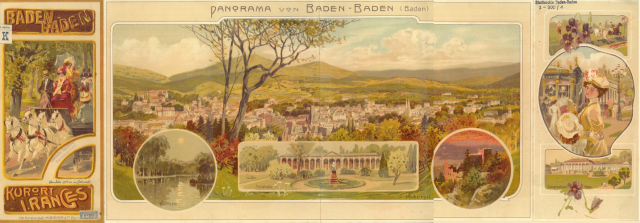

Last year, Baden-Baden was finally added as a UNESCO World Heritage site as one of eleven ‘Great Spas of Europe’.

One more reason to tell the exciting story of this spa town! As with all long stories, they have many facets. Therefore, I will introduce you to the various aspects in different modules – just read the ones that interest you the most. I will begin with a very typical aspect of a citizen’s life back then, since we are especially interested in what life looked like for your everyday person.

In the module ‘A spa day back then’, we’ll start by planning the spa treatment: which of the many accommodation options to choose, how to find them (without booking.com or google) and how to spend the day as a spa guest. Spoiler alert: it started and ended with the intake of liquids. For those interested in what they were and what happened in between, read on here.

What I find particularly exciting about Baden-Baden is that many of the buildings of that time are still standing, whether the spa buildings themselves, the theaters, hotels and restaurants, or other prominent buildings in the town. Why is that? Rumor has it that during World War 2, the U.S. Air Force mistook Baden-Baden for Schaffhausen in Switzerland, which was widely destroyed by bombs. Baden-Baden was lucky and suffered only minor damage from the war.

To exemplify this, I often juxtapose pictures of famous sights taken back then, in comparison to today!

The travel guide from 1913, a document that I have relied on for my research, lists various excursion destinations – in the module ‘Walking and strolling – excursion destinations then and now’, I present four of them to you, which can still be visited today.

My personal favorite: the ride on the Merkur Railway, which opened in 1913, up the local mountain which bares the same name.

A valid question remains why Baden-Baden in particular became the summer capital of Europe in the 19th century. In the module ‘The 19th century – from a gambler’s to a wellness paradise’ I address it, and also tell you a thing or two about famous personalities in the spa town and about the various nations that came as guests. Of course, there were also some celebrities among them! A little spoiler: Even Sisi stopped by. Find out for yourself who else came (and why…), as well as a little about the beginning of wellness as leisure activity, excuse me, I meant as a curative concept!

For those of you who want to know exactly how the city came into being and developed, I have gone back to the beginning and outline its development up to the 19th century. In the module ‘Hot springs – the origins of Baden’, you will learn what an important role the springs played in the development of the town. The ancient Romans were the first to enjoy bathing in them, and later the German emperors and other guests came for spa cures. But the town also had to cope with some crises. In the article you can read about how they were overcome and who helped to ensure that the spa town was not forgotten, but instead regained popularity as a health resort.

Of course, you can also read all the articles one after the other or chronologically – depending on your interest, desire and time! And maybe the article will inspire you to visit the city yourself and enjoy the flair of the Belle Époque: have a coffee in the Kurhaus, stroll along Lichtentaler Allee and pay a visit to the venerable Friedrich- or modern Caracalla-spa! You can obtain more information for your visit here.

By the way, the next event in Baden-Baden is the ‘World Heritage day ’ on Pentecost Sunday, June 5th. I will be there and walk through the spa gardens in historical dress with my friends from the association ‘Plaisir d’Histoire’ and I would be happy to meet some of you there. So hopefully see you soon!

- A spa day back then

How can one imagine a typical spa day in Baden-Baden in the Belle Époque times? Before the visit, the first thing that one would do was look for accommodation appropriate for one’s status. These could typically be found through advertisements in the women’s and family magazines of the time, or even calendars.

Here is a small selection of them:

(advertisements)

Or one could buy a travel guide in advance – the ones by Albert Goldschmidt were especially popular. In addition to practical hints and tips, which we will come to later, the guidebooks naturally also included recommendations for accommodations.

For Baden-Baden, for example, the ‘Hotel Stéphanie-les-Bains’ (now named ‘Brenners Park Hotel’), the ‘Hotel und Badehaus Badischer Hof’ (‘Radisson Blue’), the ‘Holland Hotel’ (‘Hotel am Sophienpark’) and the ‘Hotel Messmer’ (‘Maison Messmer’) were listed as first class hotels – all of which, by the way, still exist today! Furthermore, hotels for those with less expensive taste were listed; nowadays, we would call these ‘middle class hotels’. These were, for example, the ‘Hotel Löwen am Friedrichsbad’, the ‘Schweizerhof’ and the ‘Hotel und Badhaus zum Hirsch’.

Additionally, hotels for those with even more modest demands were also included, such as the ‘Laterne’ and ‘Hotel Merkur’. You guessed it, the mentioned examples all still exist today – although they’ve certainly undergone a renovation or another…

Furthermore, lodging houses, pensions and even private apartments could be rented (for a minimum of 8 days!) if you traveled with large family and staff.

After arriving at the hotel, one obtained a spa card, with which one was allowed to visit the spa house and garden and use all other amusement facilities.

This is what it looked like:

To get in the mood, one could stroll along the famous ‘Lichtentaler Allee’, past the ‘Sintersteinbrunnen’ with its fountain, where the trees and the parasols protected the visitors from the sun. Then the evening program began – perhaps with an aperitif in the spa park, where the orchestra played.

Afterwards one went out for dinner at a restaurant (naturally, the said guidebook recommended places to eat) such as the ‘Konversationshaus’ (deemed as ‘fine’) or for a slightly more rustic experience to the ‘Löwenbräu- Terrace and Garden’ with Munich beer. The latter still exists today, and there is still a restaurant today in the ‘Kurhaus’ (which went by the name of ‘Konversationshaus’ back then). Wine was certainly drunk there rather than beer; at the time Rhine and Moselle wines were particularly popular, along with champagne – which, however, was not quite so exclusive (and expensive) back then.

After a hopefully pleasant night’s rest, the program started quite early the next morning: after all, one was at the spa. The guidebook says about the drinking cure:

‘Approximately 2-8 or more cups (à 250g) of warm water of the Friedrichs spring (38-50 degrees Celsius) are drunk in the morning at the fountain sober…It is best to leave pauses of 10-20 minutes between the individual doses and to wait at least half an hour between the last glass until breakfast or the bath. Drinking should take place in the drinking room of the Grand ducal drinking hall with the Wandelbahn. The main time for drinking at the spa is in the morning from 6-8 o’clock. The spa guest can enjoy the experience to the sound of morning music.’

The early bird catches- well, in this case, only water!! At least there was music to go with it. Fountain cards were issued for the use of the drinking hall.

There were other springs in the spa district, such as the ‘Fettquelle’, which still exists today, but whose water is officially no longer suitable as drinking water due to current drinking water standards. In contrast, the scientific standards of that time classified it as curative.

Breakfast was well deserved and afterwards you could go swimming – the men to the ‘Friedrichsbad’ and the women to the ‘Augustabad’. Or, if the weather was nice, to a café, such as the ‘Café Zabler‘, described in the guidebook: ‘Lichtentaler Str. 12, with garden, much frequented’. That’s right, it still exists today and remains popular- only the name has changed: these days, it is called ‘Café König’.

Or you just sat down on a park bench to read comfortably.

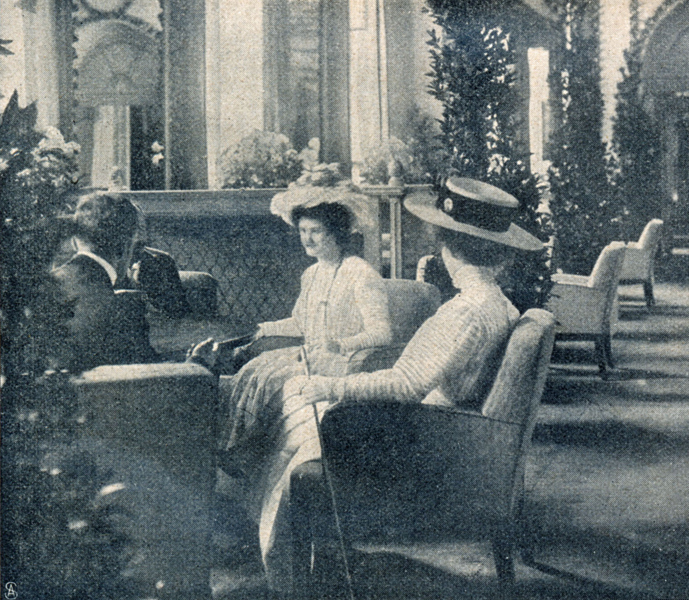

When the weather was bad, the salon of the spa house was a good alternative for a pleasant chat (such as gossip regarding who came with whom and why…). After all, better to take advantage of the spa tickets that one had paid for. There were also reading rooms, where all kinds of newspapers and magazines were kept – approx. 250, as it says in the guide book.

When one had regained strength, perhaps after a midday nap, one went back to the ‘Kurhaus’ – this time to the store in front of it (which still exists), where one could buy postcards for loved ones at home, travel souvenirs and, of course, jewelry!

Before one had to plan one’s evening program – the guests were spoiled for choice with concerts, theatres and balls – one could go for a little excursion in the surrounding area. One could either take a carriage, or, starting in 1909, an automobile, as seen below (referred to as ‘Motorwagen’, or motor car).

In the guidebook of the time, worthwhile excursions and walks were presented, along with times in which they were completed (which seem rather short to me, since everyone walks at their own pace). Here are some that are still popular today:

- Walking and strolling – excursion destinations then and now.

‘Lichtentaler Allee’ – ‘Gönneranlage’ – ‘Lichtental with monastery’

This beautiful avenue was laid out as early as 1655. First, one walks past the ‘Sinterstein Fountain’, the ‘Frieder-Burda Museum’, the monument to Empress Augusta, and admires the ‘Brenner Park Hotel’ and other historic buildings that lie along the Oos on the other side.

Further along, one passes a tennis court – the oldest one in Germany, by the way! At the time referred to as ‘lawn tennis’, this sport was practiced by women and men.

Soon the ‘Gönneranlage’ comes into sight on the right hand side of the Oos. In the middle of the garden stands the rather monumental ‘Josephinenbrunnen’ (‘Josephine fountain’), which bears the first name of the wife of the donor, the entrepreneur Sielcken. The garden was named after the mayor of the time, Albert Gönner. Nowadays, the garden is known for its roses, which bloom from late spring to fall – an impressive 360 varieties are grown there.

If you continue along the path, you’ll reach the village of Lichtental and the Cistercian convent built in 1245 which bares the same name and is still ‘in operation’. In the idyllic inner courtyard there is a store and a café, and in the convent church there are services of worship and concerts.

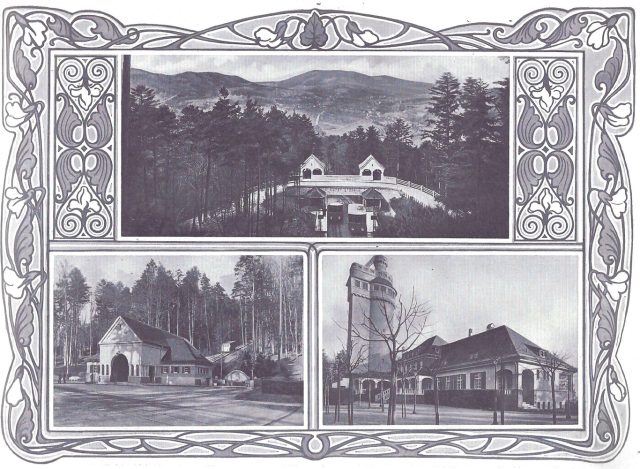

The idea of building a railway up the mountain of Merkur had existed for a long time. It first arose when the casino closed in 1872 – more attractions were needed! As the saying goes, all good things are worth waiting for, and as with many other construction projects, this was also the response at first.

But then it happened very quickly: In 1911, the railroad was approved of and built within 15 months starting in 1912. At the ceremonial opening on August 16th, 1913, all was finally well. Ever since (with the exception of a 10-year break in the 60s and 70s) it has been running continuously. With gradients of up to 58%, the railroad is one of the longest and steepest funicular railroads in Germany. Alone the experience of waiting for the train in the renovated art nouveau hall is enjoyable.

After the 5-minute ride in one of the two carriages, a wonderful view of the city, a lookout tower, a playground and barbecue area, as well as a place to stop for a bite to eat await you on Baden-Baden’s 668-meter-high local mountain. Naturally, you can also go for walks or hikes from there – or take off with your paraglider!

The castle, the ancestral seat of the Baden dynasty, has long been in ruins. Until it was moved to the ‘New Castle’ in the late 15th century, it was the residence of the Margraves of Baden. After that, it was initially a dower. In 1599, the castle was destroyed in a fire, after which it sank into a slumber and the ruin was only structurally secured at the beginning of the 19th century. Since then, it has been a popular destination for excursions; in our travel guide from 1913, the ruins are linked to a tour of the Battert (565 meters high). The description of the ruin reads:

‘At the southwestern end of the Battert, known for its jagged rocky crest (….) Hohenbaden Castle (the old castle) stands proundly on an isolated rock, surrounded by a magnificent forest.’

Fortunately, the magnificent forest still surrounds it today and the view of the city is also magnificent! Various parts of the rather large ruins can be visited, including the castle courtyard, an Aeolian (wind) harp (there was already one in Belle Époque times, but today’s is even larger) and a medieval outhouse. Back then as well as today there was and is a restaurant in the castle:

‘Larger meals require advance reservation, telephone no. 62’, it said in 1913.

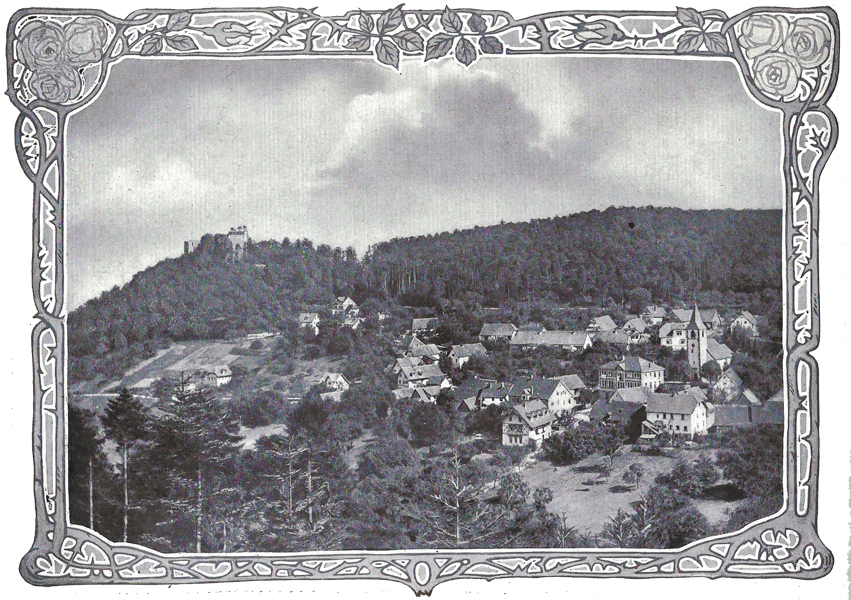

Ruin of Ebersteinburg/ Alteberstein Castle

At first the castle belonged to the count named – you guessed right- Eberstein, but due to its strategic location (and the corresponding view – more for tactical than for aesthetic reasons) it became an object of envy. According to the legend, Otto I (912-973) already had eyed it but was unable to conquer the besieged castle and therefore lured Count Eberstein to a tournament in Speyer….

Apparently, however, Otto I did not succeed in his plan, since Count Eberstein remained in possession of the castle until the 13th century. Then, it was gradually taken over by the Margraves of Baden, for whom it remained important until the 14th century. Apparently, the castle was not destroyed, but disintegrated. Today, the wildly romantic ruins can be climbed either from the nearby village of Eberstein or on hiking trails from Baden-Baden – also via the Hohenbaden Castle presented earlier, by the way!

A curious fact: trout farming is already recommended in the guidebook from 1913, and has existed since 1877:

‘The upper Oostal is known for its unique natural beauty (…), further up, the valley narrows significantly; sideways towards the Murg another valley appears, and in foreground, it seems as if the increasingly dense rocks are closing together; here is the highly frequented Gaisbacher fish farm (excellent trout, restaurant and pension, climatic spa). A visit is highly recommended.’

Nowadays it is possible to reach the farm by bus, but you can also still walk there and visit the facility.

- The 19th century: From gambler’s paradise to wellness heaven

At the beginning of the century, the number of guests increased and the state government took notice. It took over the Promenadehaus and appointed its architect Friedrich Weinbrenner (1766-1826), who had already proven his potential in the residential city of Karlsruhe, to extend the building.

In the following years he was to play an important role in the city not only as an architect but also as an urban planner. Under his direction, a Capuchin monastery was transformed into the hotel ‘Badischer Hof’ – one of the earliest ‘first-rate’ grand hotels, which naturally attracted wealthy visitors! In addition to a huge dining room, it had a ballroom and its own bathing cabins and other spa facilities, connected through its own water pipe from the hot springs.

However, Weinbrenner is best known for the construction of the new ‘Conversation House’. In the surrounding springs district, he had already rebuilt a conversation house from an existing Jesuit college in the years before and built a ‘Trinkhalle’ (‘drinking hall’) in 1823; both buildings no longer exist.

Additionally, some private buildings were built under his supervision – located in the floodplain of the river Oos, where the later spa buildings were to be built later. These included a summer palace for Queen Friederike of Sweden on ‘Lichtentaler Allee’, today’s ‘Kulturhaus LA8’, and the ‘Palais Hamilton’, which can be described as the first sophisticated city palace. Originally built around 1808 for the wealthy country doctor Mayer, it was passed on via Grand Duke Leopold to Napoleon’s adopted daughter Grand Duchess Stéphanie (she had married Grand Duke Charles of Baden, but he died young). The name of the palace comes from Stéphanie’s son-in-law, Duke Hamilton, who had married one of her daughters, Marie. The house can still be admired today at Sophienstrasse 1 and it now houses a bank.

Another quick note on the architect Friedrich Weinbrenner: His classicist style became known beyond the borders of the country and he was one of the first preservationists! Weinbrenner was committed against the demolition of medieval buildings; for instance, he fought to preserve the city gates of Baden-Baden – in this case unfortunately without success.

His newly built conversation house was a white elongated three-part structure with symmetrical forms – at 140 meters long, it was the largest building erected in Baden-Baden to date. The central section with its porch supported by Corinthian columns was preserved more or less true to the original, while the two sides were structurally altered over the years. The display front facing the city attracted a lot of attention.

Inside, there was a ballroom, gaming salons, a library, a restaurant and a theater – entertainment was certainly provided for!

In the course of construction, the park area to the east and south of the house was also landscaped.

The French – good guests and businessmen

Frenchmen began to arrive as exiles during the French Revolution to settle in the city. These created favorable conditions for further guests to follow suit. Naturally, it was also the proximity to Paris that made Baden attractive to French spa visitors. In addition, there were other events that drew well-to-do Frenchmen away from their own country to Baden: the July Revolution of 1830, a cholera epidemic the following year, and most importantly, the ban on gambling throughout France in 1837.

In Baden, gambling had been allowed since the beginning of the 19th century. At first, roulette was played in the main hall of the ‘Kurhaus’ (which initially went by the name of ‘conversation house’), which was called ‘hazard game’ at the time, and cards were played in other rooms.

It was mainly French leaseholders who successfully developed and skilfully managed the casino and the conversation house. Foremost among them was Jean Jacques Bénazet, who was able to build a dynasty in the city through his business skills, whose members were to become important patrons for the city. Certainly, a little self-interest was also a factor – they had understood that their business success was linked to the further development of the spa town of Baden.

Interestingly, the revenues of the casino and the ‘Kurhaus’ were heavily taxed – the entries went into a ‘Badfond’ (spa fund), which was explicitly collected for the development of the town and maintenance of its public facilities.

The new drinking hall (‘Trinkhalle’) – stroll around, drink and be seen!

This also made it possible to build a new drinking hall in the immediate vicinity of the ‘Kurhaus’. This was also done in order not to completely neglect the spa character of the town: One had to have an official reason for the pleasurable stay, after all!

It was built from 1839 to 1842 by Heinrich Hübsch, a pupil of Weinbrenner’s. In the building, built in the style of late Romanticism, one could fill one’s cup of thermal water in the fountain room, then walk through the colonnades and look at the fourteen painted pictures (by J. Götzenberger) with legends of the surrounding towns. The water was known for its high lithium content, which was said to help against all kinds of ailments and aches, such as gout and metabolic disorders. Today the water, which still bubbles freely at some springs, is mainly used for external applications.

International visitors – who came and who left?

More and more guests came, not only from France. While the number of visitors increased modestly from 1806 to 1830 from about 1000 to 11,000 guests, the number tripled to about 33,000 guests by 1847 and increased again by almost the double to over 62,000 annual visitors by 1869.

Not only guests from France liked to come, but also many Englishmen, Russians and Americans, who also made their mark on the city. And not to forget Germans! Apart from the fact that gambling was equally forbidden in some German countries, it simply became en vogue for aristocrats and wealthy commoners to spend a ‘curative’ summer in Baden-Baden.

Each nationality brought its religion and consequently, many other churches were built in addition to the already existing Catholic and Protestant churches. These included a Russian Orthodox church, the church ‘St. Johannis’ for the English-speaking visitors (even the English Queen Victoria donated for the construction!) and, at the end of the 19th century, a synagogue, which was unfortunately destroyed in 1938 during the pogrom – all other churches mentioned exist to this day, seen in these pictures:

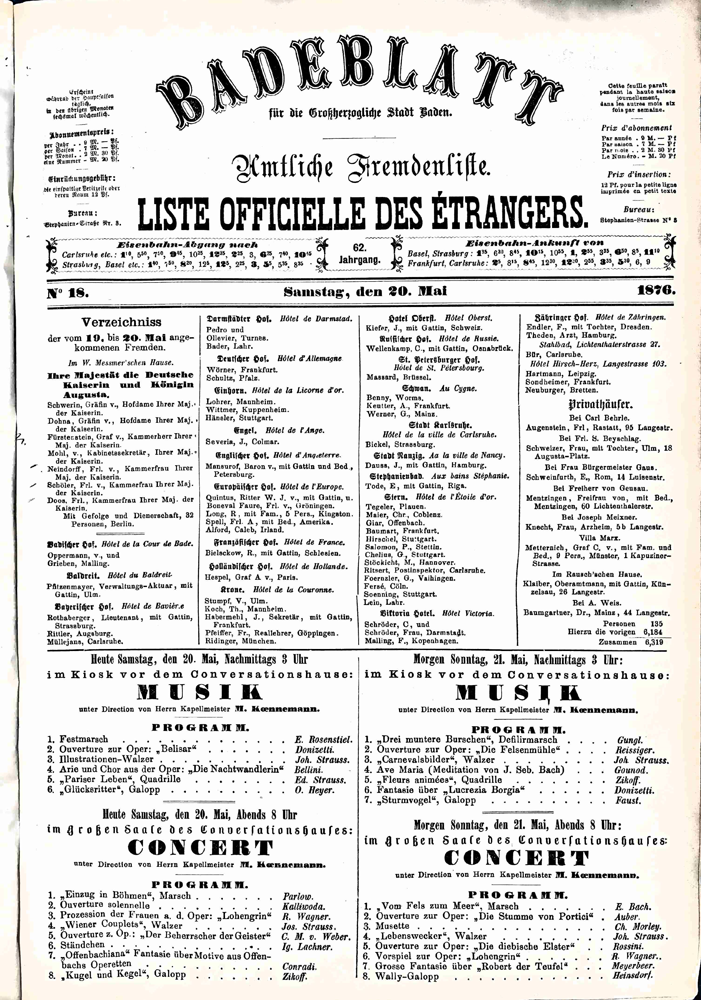

A detailed account of which German and international guests came was recorded in the ‘Badeblatt’, which included lists of who stayed in which hotel or pension/villa, moved and left again.

Particularly interesting in the past and today:

The celebrities: kings, empresses and all kinds of luminaries

The up-and-coming summer capital naturally also attracted celebrities, which made it even more popular. These included the Prussian King Wilhelm I and his wife Augusta, who was particularly fond of Baden-Baden and felt more at home there than in her obligatory home of Berlin.

Two monuments testify to the fact that Baden-Baden held both of them in high esteem: The bust of the empress was unveiled two years after her death, in the ‘Lichtentaler Allee’ in 1892, where it has stood ever since (only now somewhat further south). A bust of Emperor Wilhelm I can be found in front of the ‘Trinkhalle’.

The Austrian Empress Sisi also stopped by from time to time, but remained incognito. She came to visit her sister Mathilde, who had been a temporary resident of Baden-Baden since 1880.

Mathilde had married the Prince of Naples-Sicily, later Count of Trani, and thus the brother of her brother-in-law, the last King of the Two Sicilies, the husband of her elder sister Marie. Their unhappy marriage produced a daughter, Princess Maria Theresa. When she married in 1889, her excerpt from the church was a major social event in the city.

After a serenade in front of her house in the presence of Grand Duke Frederick and his wife Luise, Empress Augusta, who was (coincidentally?) present, personally hosted a soirée at the ‘Hotel Messmer’ before the bride traveled to her groom the next day by rail in a state-owned magnificent carriage.

Composer Clara Schumann loved to spend summers in the city, especially when her friend, composer Johannes Brahms was around. They were welcome visitors in the salon of the versatile musician Pauline Viardot, who played an important role in helping to develop Baden as a highly cultural city: With salons and soirées, she brought together the creative artists and cultural workers, and even founded her own opera house with the ‘Theatre Viardot’, a garden theater and an art and lecture hall. It can be said that her work helped to establish the musical tradition of the city.

Not only musical celebrities met in her salon, but also poets and thinkers as well as other ‘bright minds’ who frequently stayed in the city. Among them were famous figures such as Theodor Storm and the Russian writers Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Turgenev. There were rumors in town about a menage á trois between Viardot, her (much older) husband and the (much younger) Turgenev. Nothing is known for sure, but it should be noted that Turgenev had already followed the Viardots to Paris and then to Baden-Baden. Then again, it may have simply been a creative working relationship between the three of them…

Writers like Dostoyevsky were not only in the city to write, but also to gamble – his novel ‘The Gambler’ was certainly influenced by some his own experiences in Baden-Baden…

In the course of the 19th century, the spa town became somewhat of a playing ground for many other famous writers, including the American Mark Twain, the Englishmen William Thackeray and Mary Shelley, and the Frenchmen Alexandre Dumas and Honoré de Balzac.

Gambling and other amusements

Even though the casino was an important reason for many guests to visit Baden-Baden, it was not the only one. Even the French tenants of the casino and ‘Kurhaus’ were anxious to create other attractions that would delight guests and perhaps induce them to stay longer.

‘Kurhaus’ – Gambling in the ambience of the Sun King

The ‘Kurhaus’ became even more splendid in the 1950s: luxurious ballrooms and magnificent gambling halls were created in the Baroque and Rococo styles. Four rooms have been preserved: the Louis XIII and Louis XIV halls as well as a ‘Salon Pompadour’ and a conservatory in the Louis XVI style. At first, people gambled in them, later they danced, and today? They do both!

Theater

The profits that were won from the casino and the ‘Kurhaus’ must have been considerable, for the leaseholder Edouard Bénaret donated a new theater to the city. Built in 1860-62 according to the plans of French artists Charles Derchy and Charles Couteau, the exterior was built in the Neoclassical style, while the interiors were designed in the playful Rococo style. For its opening in August of 1862, the opera ‘Béatrice et Bénédict’ was composed especially by Hector Berlioz! Not only operas were performed there, but also many concerts. Today, the theater is one of the oldest theaters in Germany that is still in operation – and one of the most beautiful! In addition to classical plays, the theater’s own ensemble also performs modern plays.

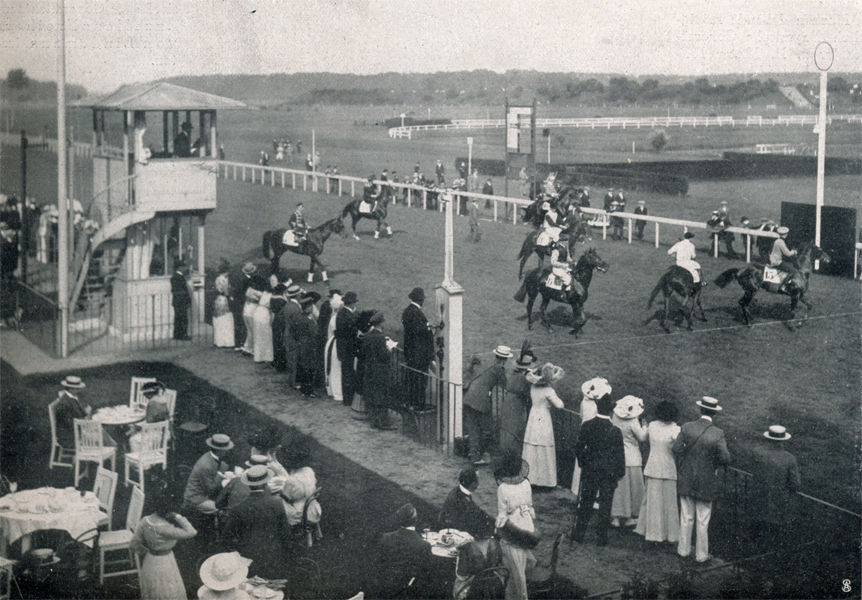

Horse racing

Also initiated by Edouard Bénazet, horse races have been held at the racecourse in nearby Iffezheim since 1858. This was always a social highlight and an opportunity for the ladies to show off their latest hats! The Baden ‘Great Week’ takes place annually at the end of August/beginning of September – until today.

These additional entertainment venues became all the more significant when an important attraction for spa guests disappeared in 1872. The sovereign Friedrich von Baden already wanted to prohibit the gambling operations at the beginning of the 1860s, and the ban was finally decided by the North German Confederation in 1867. The concession was extended until 1872, but then it was over: the casino had to close.

The city needs new baths!

The city’s leaders thus had several years to come up with new concepts to maintain and expand the appeal of the city to paying guests. Back then as well as today, one had to keep up with the times: observe new trends and implement them! One such trend was that health, hygiene and sports were becoming increasingly important, and not just for the sophisticated members of society. People realized that hygiene was vital for preventing disease and that maintaining one’s own health was important – and with it how they dressed, ate and how they could take care of their body. This included applications for health (we would say wellness treatments today) and also sports. Industrialization had increased the number of people who no longer worked primarily physically, but in ‘bureaus’ and offices. As a form of compensation, they needed exercise in their free time!

In Baden-Baden, it was decided to build the Friedrichsbad. Constructed in the Renaissance style, it was to be the most modern bathhouse in Europe when it opened in 1877!

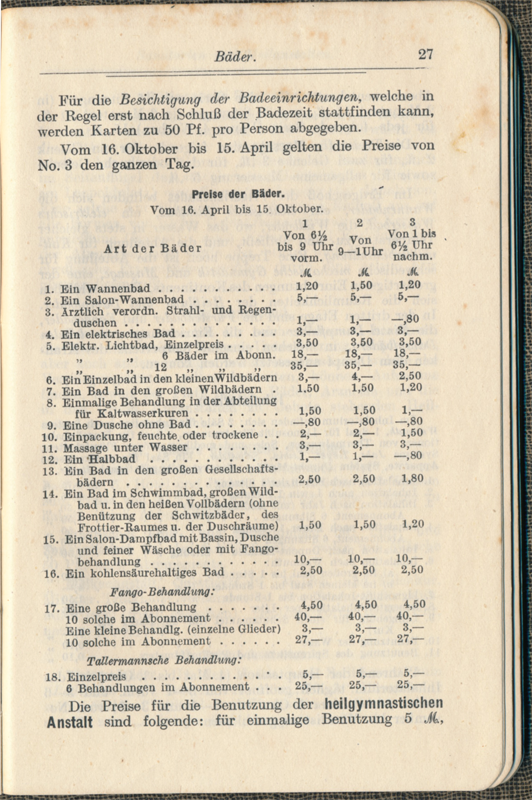

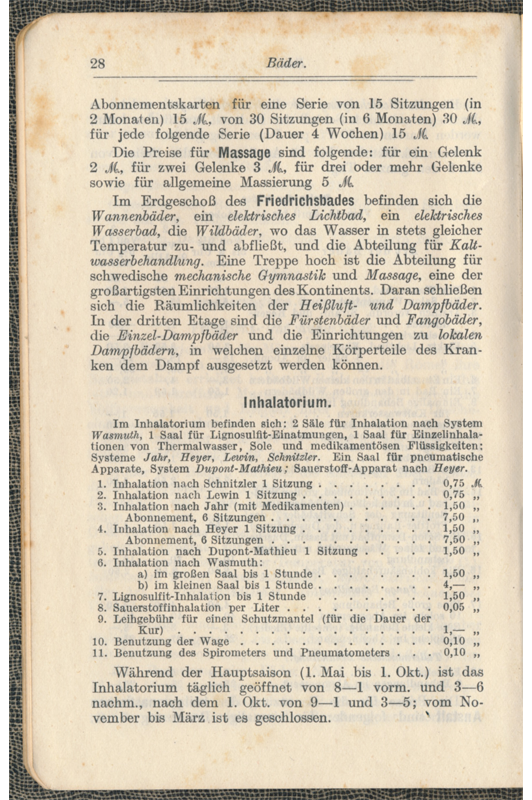

The various options for baths and treatments (and how much they cost) are shown in this excerpt from a spa brochure.

In the Friedrichsbad (named after the ‘Landesvater’, or state father at the time, Grand Duke Friedrich) there was also a gymnastics hall with equipment. Here is a description from the Baden-Baden guide from 1913:

‘…Up one flight of stairs is the department of Swedish mechanical gymnastics and massage, one of the grandest facilities on the continent.’

Initially, the baths were designed for both men and women. Following the antique tradition, the bath was separated into a men’s and women’s unit, and bathing was therefore done separately. Despite the high prices, the bath soon reached its capacity limit.

Thus, the counterpart for women was built from 1890-1893 in the immediate vicinity of the Friedrichsbad (this was necessary due to the location of the springs), and was named the ‘Augustabad’ after the German empress. The interior design was similar, and both baths charged the same prices.

While one can still enjoy a bath in the ‘Friedrichsbad’ today, the ‘Augustabad ‘was demolished in the early 1960s.

Instead (and also in close proximity) there is now the ‘Caracalla-Therme’ as a modern counterpart to the time-honored ‘Friedrichsbad’.

In the following module, you’ll discover that the springs have been used for a long time:

- Hot springs – the origin of Baden.

Everything began with the discovery of the hot springs – they are somewhat of a constant in the development of the city.

The original name of the Roman settlement that developed around these springs around 70 A.D. is still a matter of debate today. However, what is certain is that two Roman baths have been preserved: The imperial baths near the collegiate church and the marketplace, discovered in the mid-19th century during the construction of the steam baths (which acquired their name because they were more splendidly furnished), and the rather meager ‘soldier baths’, discovered during the construction of the Friedrich and Augusta baths, the ruins of which can still be admired today near the ‘Friedrichbad’. It is believed that the Roman settlement was a place where soldiers were sent to recover- hence it name, ‘soldier’s baths’.

Perhaps it was the Roman Emperor Caracalla who had the baths expanded and renovated; after all, today’s modern baths bear his name. Remains of the Roman settlement are still preserved.

The Romans were driven out by the Alemanni. Unfortunately, there are no written records from that time. However, the first record following antiquity was a donation from 987 by Otto III, in which the place is referred to as ‘Badon’ – that sounds quite similar already!

The nearby Hohenbaden Castle, which can still be seen as a ruin above the town, is mentioned for the first time in 1122 – it was most likely built around 1100, probably by Hermann I, progenitor of the House of Baden. In 1112, his son, Hermann II, was called ‘Margrave of Baden’ for the first time, which can be regarded as somewhat of a birth certificate of the Margraviate of Baden and the Baden dynasty. From 1150 Baden developed urban structures and not too long after -from about 1306 onwards- the thermal springs were used (again) for baths!

At first, the city became a health resort for bathing cures. One lay in the baths for hours, which according to the state of knowledge at the time was very healthy – or perhaps mainly relaxing… Emperor Charles Frederick III already traveled to Baden for a bathing cure in 1473.

In 1535, the Margraviate of Baden was divided into two parts according to hereditary division laws and these new parts were called after the names of the towns they were situated in, namely Baden-Baden and Baden-Durlach. Over the course of time, the city of Baden received various additions to its name, such as ‘Baden in Baden’ in order not to confuse it with other existing cities in Austria and Switzerland with the name of ‘Baden’, before it finally became ‘Baden-Baden’ in the 19th century.

The city experienced a tragedy with the Nine Years’ War. In 1689, it was burned down by French troops; naturally, the bathing business came to a standstill and did not really get back on its feet after the reconstruction. In addition, Baden was suddenly no longer a royal seat. Its ruler Ludwig-Wilhelm of Baden, also known as ‘Türkenlouis’ due to his successful campaigns in the Ottoman Empire, wanted to have a palace built following the Versailles model.

Unfortunately, this was not possible in Baden-Baden and the project was carried out in Rastatt, which consequently became the royal seat in 1706. The reconstruction of Baden-Baden was slow, the bathhouses and hostels were unfashionable, and the cityscape was not very well-kept. Another reason that the bathing cures fell out of fashion: Both sexes often bathed together and thus all kinds of diseases were transmitted – this went against the idea of a curative and hygienic activity.

Before the city disappeared completely into insignificance at the end of the 18th century, it was rediscovered by the state of Baden when Elector Karl Friedrich chose it as his summer residence in 1805. As a result, visitors flowed in once more – a good reason to develop it as a sophisticated spa town! The first step that was taken to make the town more attractive again for paying and especially well-heeled guests was the construction of the ‘Promenadehaus’.

Furthermore, the bathing cures, which were out of fashion, were increasingly replaced by drinking cures – not only thermal and mineral water cures were offered, but also ‘whey cures’.

Thus, the well-heeled aristocratic and bourgeois public now could come on the basis of their ‘health’, but simultaneously enjoy themselves AND gamble.

You can learn about how Baden continued to develop in the 19th century in this article: ‘The 19th century: From a gambler’s to a wellness paradise’.

I would like to express my sincere thanks to all the contributors who supported me in the creation of this article!