Kingdom of Saxony – from pompous state to industrial stronghold

‘A Schaelch´n Heeß´n” (dialect word for “a cup of coffee”), ‘Quarkkeulchen’ (speciality: kind of sweet cottage cheese pancakes) and ‘Bemm´n’ (dialect word for sandwiches) Saxony, the former kingdom which is today the Free State of Bavaria, is not only known for its distinctive dialect – which used to be Germany’s official language from the 16th to the early 18th century! It was known as ‘Meissner Kanzleideutsch’, meaning the chancellery language of Saxony, and was spoken widely; Luther also translated the Bible into Saxonian. After the Prussians won a war against the Saxons, the Prussian dialect took its place. But the relationship between the Saxons and the Prussians is a story of its own …

Saxony is primarily known for its metropolises, its rulers and its art monuments.

The history of this state is diverse and rich in anecdotes. We will present some of them here: from an electoral prince, who had the ability to break horseshoes and who was said to have had affairs with 120 women, from another who protected Luther and thus saved the Reformation, and from the last King of Saxony, who became a modern, single father of six children after his wife left to Switzerland…

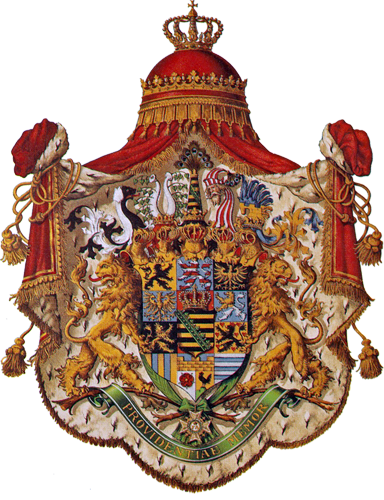

And from a strong noble dynasty, the House of Wettin, to which all these rulers belonged.

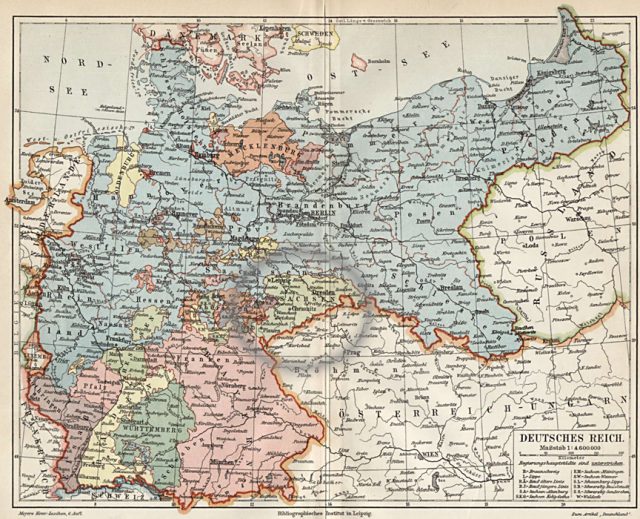

Firstly, let’s find the kingdom of Saxony in the German Empire by following a description of the Regional Studies of the State of Saxony from around 1905:

‘The Kingdom of Saxony lies in the middle of the German Empire and yet also on the border of the Empire, as the Austrian Crownland of Bohemia is placed like a large wedge between Silesia and Bavaria. The most eastern point of Saxony is 220 km from the Russian border and the most southwestern point is 400 km from the French border. From north to south, Saxony is equally distant from the sea and high mountains, as it is 235 km from the foot of the Alps on Lake Chiemsee, and 225 km from the Baltic Sea port of Szczecin.’

After having placed the Empire within Germany, between Russia and France, as well as between mountains and the ocean, let’s have another look at the states that border Saxony:

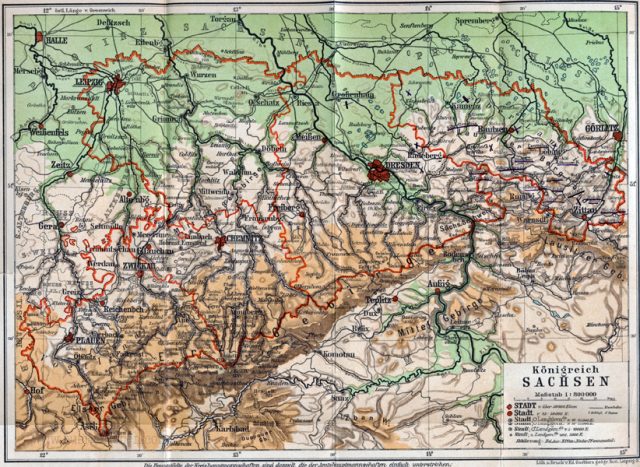

Saxony has natural borders only in the south, where the state border tends to follow the ridge of the mountains and is the border with Austria (with a length of 487 km). In the east, north and north-west, the Prussian provinces of Silesia and Saxony (yes, treacherous, this Prussian province of the same name) make up the border with Saxony with a length of 424 km; in the west, it has Thuringian states as neighbours for 285 km, compromising of the Duchy of Saxony-Altenburg, the Grand Duchy of Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach and the two Principalities of Reuss (Article about Reuß older line) and the Kingdom of Bavaria as a neighbour for 30 km.

As in the Grand Duchy of Baden, there were also exclaves and enclaves in Saxony, which meant that on the one hand there were places within its territory which belonged to other states, such as the village of Russdorf near Limbach, which was an exclave of Saxony-Altenburg. On the other hand, there were places outside of Saxony which belonged to the Saxonian kingdom.

Saxony was the fifth largest state in terms of size, with a slightly smaller territory (approx. 1500 km2) than Baden, but it was third in terms of population, with 4.2 million inhabitants. The largest cities in the kingdom were (as of 1905) after Dresden (514,000 inhabitants): Leipzig (503,000), Chemnitz (244,000), Plauen (105,000) and Zwickau (68,000).

In order to explore how the borders in this state developed, we will take:

A look back

First, let’s look back at the country’s history. In order to better understand this story, the Saxonian princely procession, which can be admired as a picture in Dresden, is very helpful! It pictures all rulers of Saxony, united in this royal procession – except for the last King of Saxony, who was not yet in office when the picture was created.

A brief note on the image of the princely procession: The 102-meter-long image consists of approximately 23,000 tiles made of Meissner porcelain, making it the largest porcelain image in the world! It was installed in 1907 on the outside of the stable yard of the Dresden Castle in its current form. The first frieze of images was created at the end of the 19th century, but it was not yet weatherproof and therefore it was made again with tiles.

Of course, we cannot look at all of the 34 margraves, dukes, electoral princes and Kings of the Wettin family depicted on the image; hence, we will focus on those who as rulers helped the state of Saxony progress, were important for other reasons or are remembered due to other characteristics .

But where did Saxony originate from? It began on a castle in Meissen (also known as Misina or Misni), built by King Henry I on a rocky plateau at the mouth of the Triebisch into the Elbe, constructed to permanently rule and secure the formerly Slavic country. The Margravate of Meissen was named after it and became the ‘cradle of today’s Saxony’. Margravate meant the bordering zone, as the Elbe was the natural border.

Konrad I (1098-1157), called ‘the Great One’ (or ‘the Pious One’),

led the prince’s procession. As the Count of Wettin, he grew up as legitimate heir to the Margravate of Meissen and Margravate of Lusatia, as his cousin Heinrich, the former ruler of these areas, had no heir at the time of his death. However, his wife gave birth to a boy, Henry II, shortly after his death. It was rumoured that she gave birth to a girl and that the child was exchanged for a boy not of noble origin. Konrad made fun of Henry II, who was made the heir to the throne.

Henry II was not amused by this and had Konrad locked up. This would have been the end of the story and Konrad would have long been forgotten and left to rot in prison, if fate had not meant it differently: Henry II died unexpectedly at the age of 20 – it was rumoured that he was poisoned. And so Konrad was freed and able to come into power! However, he was not able to take over right away, as the emperor did not give the fiefs (Margravate of Meissen and Lusatia) to him, but to an old follower of his. Thus, Konrad teamed up with the mighty Saxon Duke Lothar and Albrecht the Bear and thus overthrew the Margravate of Meissen and later also that of Lusatia. Over time, he expanded his territory even further. Konrad is therefore considered the actual founder of the power of the Princely House of Wettin.

Incidentally, he was also a good diplomat. He was able to expand his power through clever marriages; for instance, he married his son Dietrich off to the daughter of a Polish duke in 1146, which allowed the tense relationship with the Kingdom of Poland to relax after the war. Other children of his were also married off into powerful dynasties.

And why was Konrad also called ‘The Pious One’? It was due to his good relationship with the church, which he upheld during his rulership; probably not because he was so pious, but rather as a way to secure his rule. And so it was no coincidence that his nephew was chosen to be one of the influential archbishops of Magdeburg.

Finally, he entered the monastery as a lay brother at the age of almost 60 – so was he a true believer after all? Possibly, but there was more to this decision: It allowed him to divide his property among his five sons while he was alive and also pass on the fief Meissen. He died barely six months after he had entered the monastery and after all of his affairs had been settled. He has been remembered not only as a leader in the image of the princely procession, but also as the founder of the power of the Wettin House.

Saxony gets a university and becomes an Electorate – with Friedrich IV. – called ‘The Quarrelsome One’ (1370-1428)

Friedrich IV was already forward-looking when he held the position as the margrave of Meissen. When German scholars and students left the oldest German-speaking university in Prague, which had existed since 1348, due to national political tensions between what was then Bohemia and the Wettin region, they took up residence in the nearby Leipzig. Thereupon, Friedrich IV quickly founded the first Wettin state university in Leipzig with his co-governing brother Wilhelm II (called ‘The Rich One’). With the Pope’s permission, the university began teaching students in 1409. The university not only enhanced the status of the city of Leipzig, but also of the entire territory. At the time, Friedrich IV had fought against the Hussites for the German King Sigismund. As a reward, he received the Duchy of Saxon-Wittenberg from the king. While the Duchy itself was neither particularly large nor significant, the Saxon-Wittenberg princes were among the seven electors, according to the golden bull of 1356.

The electors elected the emperor and thus had the most prestigious position among the imperial princes. This transfer was possible because the previous ruling Ascanian family had died out. Friedrich IV became elector and called himself ‘Friedrich I.’

Incidentally, these events also made the name ‘Saxony’ common for the region. Originally descending from Lower Saxony, the name shifted upstream to the southeast and was used as a designation for the now Wettin areas in the former areas of Meissen, Thuringia and Upper Lusatia.

Two brothers rule together – before they split the country

Friedrich II’s successor left two sons, Ernst (1441-1486) and Albrecht (1443-1500), who initially governed the country together after the death of their father; Ernst as Elector and Albrecht as Duke. Their government was a peaceful coexistence – the two had been particularly close since childhood. The two of them had been victims of a dramatic kidnapping in 1455! During the so-called Altenburg prince robbery, Knight Kunz had kidnapped 14-year-old Ernst and 11-year-old Albrecht from Kaufungen with some accomplices from the Altenburg castle in order to enforce his claims for compensation for lost lands. There are different theories about how the kidnappers were caught, but one thing is certain: the kidnappers were overpowered, arrested and severely punished! Knight Kunz of Kaufungen was sentenced to death five days after the kidnapping in Freiberg and beheaded on the Freiberg Upper Market (the spot towards which the head supposedly rolled is still marked with a blue paving stone today) and his helpers were equally severely punished: the kitchen assistant from the castle, Hans Schwalbe, was first pinched with glowing tongs and then quartered. Different times, different penalties!

Despite the harmonious relationship between the brothers, Ernst urged his younger brother Albrecht to divide their land. The division was decided in Leipzig in 1485. Ernst (after whom the Ernestine line would be named) retained the electorate and got the areas around Wittenberg and Torgau with a subsequent strip of land via Altenburg and Zwickau to the Vogtland region and most of the Thuringian area.

Albrecht (after which the Albertine line would be named) got the Meissen part with Dresden, Freiberg and Chemnitz, areas around Leipzig and the northern tip of Thuringia.

The division was intended to weaken the power of the Wettin House in the Empire. Up to this point they were the strongest German territorial power after the Habsburgs, but became less powerful due to the division into two parts.

As previously mentioned, we can only outline the story through milestones. Another milestone that must be mentioned is the role of

Elector Friedrich III, the ‘Wise One’ (1463-1525).

As the son of the older brother Ernst, he ruled the country (i.e. the Ernestine part) for a long time – almost 40 years. At the University of Wittenberg, which he founded, a young theologian who was appointed professor caused a stir in the last quarter of his reign. His name: Martin Luther. Thus, the development of the two Saxon states became significant again for the fate of all of Europe, since even then wars were waged over religions. When Luther came under threat for his revolutionary theses, which Rome declared to be heretical activities, the electoral prince stood by him. He did not deliver him to Rome, but rather gave him free escort for crucial interrogation at the Worms Reichstag in 1521 and brought him to safety after the imperial ban on the Wartburg near Eisenach. There Luther was able to translate the Bible into German undisturbed under the name of Junker Joerg.

Friedrich III only converted to the new teaching on his deathbed. His successors, initially his younger brother

John the Steadfast (1468-1532),

introduced the Reformation in the electorate of Saxony. His son

Johann Friedrich I. (1503-1554)

also pursued the Reformation course as his successor. He was even involved in leading a defensive military alliance of countries, the Schmalkaldic League

(named after the place where the princes meet, called Schmalkalden), which were evangelical (i.e. reformatory).

The emperor Charles V opposed this belief. He decided to launch a campaign against the new Protestant faith and the countries that adhered to it. The campaign ended with a crushing defeat of the countries united in the Schmalkaldic League. This had serious consequences for Johann Friedrich and his part of the country: he lost the electorate and was imprisoned by the emperor for years. Significant parts of the country were changed by the state division: Johann Friedrich only retained the Thuringian part west of the Saale. When he was released in 1552, Weimar became his residence. Even this area was increasingly fragmented under the rule of the Ernestine Dukes of Saxony: when the German Empire was constituted in 1871, four small states with Saxony were included in the title: the Duchies of Saxony-Meiningen, Saxony-Altenburg, Saxony-Coburg and Gotha as well as the somewhat larger Grand Duchy of Saxony-Weimar-Eisenach, which will be discussed in further articles.

And the Albertine part? A successor of Albrecht’s also introduced the Reformation there, namely

Heinrich, the ‘Pious One’ (1773-1541).

The titles based on characteristics do fit! However, his successor was

Duke Moritz (1521-1553),

who apparently had no name attributed to him based on his character, but if he would have been assigned one, it would have been ‘The Ruthless One’, as he was always hungry for power and jealous of the electoral dignity of his cousin Johann Friedrich I. In the struggle against the Schmalkaldic League, he sided with the Emperor, despite his Protestant belief. Morally reprehensible, but tactically clever. He received the electorate and, due to the revised division, exactly the areas that his cousin Johann Friedrich I, captured by the emperor, had to give up: the entire Kurkreis with Wittenberg and Torgau as far as Zwickau.

By the way, he later turned himself against the emperor, as the leader of an alliance of North German Protestant princes. In the end, in the Passau Treaty of 1552, Moritz was able to end the religious disputes and have the Protestant faith recognized by the emperor. His successor,

Elector August (1553-1586),

Was able to reduce the enormous debt that Moritz had left behind thanks to his clever management of the budget and a skilful economic policy, but also continued the development of the electorate as a modern state, away from the medieval structures. A Court Council was created as a body for legal, domestic and foreign policy issues. While the emperor had made use of it at first, the court council acted increasingly independently, which was accepted. Jurisdiction was more uniformly regulated, and many new regulations were issued, including a coin regulation, a forest regulation, a school regulation and several mining regulations. Mining was further developed and promoted as an important source of income for the state.

Elector Johann Georg I, ‘Beer- Joergl’ (1611-1656)

Until then, the Electorate of Saxony had been one of the strongholds of the Protestant faith (albeit in different forms), but this changed with the reign of Johann Georg I.

He had many chances – the riots in neighbouring Prague in 1618, during which the Protestant Bohemian estates rebelled against the Habsburg, made him the new king of Bohemia. And in 1619, Johann Georg I was even considered as a potential new German emperor. And what did he do? Declined both offers, because his passion was drinking beer rather than doing politics – consequently he was nicknamed ‘Beer- Joergl’. And not just this- he also supported the Catholic Habsburg imperial house against the struggle of the Bohemian Protestants. This was perceived as a betrayal by Protestants outside of Saxony, and rightly so. However, Beer- Joergl was rewarded by the emperor – he received the area of Upper and Lower Lusatia, first as a pledged possession (in return for borrowed money), later as a Bohemian loan (goods that could be inherited).

The riots in Prague (second Prague defenestration in 1618) were also a cause of the Thirty Years’ War, which started in 1618 and was to affect all of Europe. Due to the neutrality of Johann Georg I. towards the emperor, the country was initially largely spared from the chaos of war. However, when the imperial troops destroyed Magdeburg in 1631 and General Tilly began to invade the Electorate of Saxony and take over Leipzig and Merseburg, the public pressure on him increased. He had to act and joined the Swedish king Gustav Adolf. The Saxon army initially united with the Swedish troops, a problematic alliance, which was soon cancelled by the Saxon side. Instead, they arranged themselves with the Habsburg imperial state and in 1635 (together with the Elector of Bavaria Maximilian I) decided on the Prague Peace.

However, the country was subsequently devastated by the Swedes and imperial troops passing through. There were also arsons, lootings and epidemics – this decade was to be the worst in the entire history of the Electorate. In 1645, Saxony left the war with Sweden (the Armistice of Koetschenbroda), but it was to take three more years until there was finally peace, in 1648, with the ‘Peace of Westphalia’. It had the following effects on the Electorate of Saxony: it retained the Upper and Lower Lusatia acquired during the war; however, the coveted Archdiocese of Magdeburg went to the Electorate of Brandenburg.

And Beer- Joergl? With his actions he had not only gambled away the reputation of Saxony as the supreme power of German Protestantism, but also had his land divided among his four sons. This gave rise to three smaller principalities: Saxony-Weissenfels (until 1746); Saxony-Merseburg (until 1738) and Saxony-Zeitz (until 1718). If these new Albertiner branch lines had not died out in the course of the 18th century and thus reverted to the main Dresden line, the Kingdom of Saxony would never have existed!

We can ignore some of the subsequent princes (Johann Georg II. to IV.), A nice summary in a 1913 document on the history of the kingdom states:

‘All these princes ruled little in the spirit of Augustus’ father. They loved splendid hunts and brilliant court festivals.’

After that, however, came a ruler who is still very well known today and after whom an epoch, the ‘Augustinian Age’, was named:

August ‘the Strong’ (1670-1733),

followed his brother Johann Georg IV to the throne. As the name suggests, he was strong – today you would say fat, because he weighed over 120 kilos. But that corresponded to the baroque ideal of beauty at the time. It is said that he also demonstrated his strength with the breaking of horseshoes – it was later examined and turned out to be a ‘faulty batch’, as the director of the Green Vault, Prof. Dr. Syndram, noted.

His strength was also related to his appeal to the ladies- he was said to have had affairs with over 120 women and fathered 354 children. Only nine children have been handed down and documented, including his official son.

He had three children with Countess Kosel, probably the best known of his mistresses. In a weak moment he had given her a written marriage promise. However, this was to doom her, because when his love for her faded, he sent her to the Stolpen Castle in forced exile where she would live for 39 years, until her death.

He was married to the Brandenburg princess Eberhardine (1671-1727), and together they had a son as heir to the throne. It was marriage principally organised for tactical reasons (to strengthen the bond between the powerful families of the Wettin and Hohenzollern families). Eberhardine, at least, loved her August at first, as can be seen from letters – but he enjoyed himself outside of their marriage early on. She was very religious and when her husband changed his denomination and converted to the Catholic faith to become king in Poland, the couple finally separated – she was outraged, remained Protestant and retired to her Pretsch Castle, which he had gifted her when she bore him their son.

Yes, the king was hungry for power – he wanted to be one of the top monarchs in Europe. When he had the chance to be crowned king in Poland, as in Poland there was no succession to the kings and so the new king could ‘apply’, he was successful and was chosen by the Polish nobles. But how did you win them over? With a bribe, taken from the state treasury and ensuring that other potential candidates for the throne could not compete. After August accepted the Catholic faith as a further prerequisite for the title, he was crowned King of Poland in 1697 and henceforth called himself ‘August II.’

In terms of power and splendour, August’s great role model was the French sun king, Louis XIV. His residence city of Dresden was not to be in any way inferior to Louis XIV’s , and so he had magnificent baroque-style buildings erected that still make up the face of the city as ‘Florence on the Elbe’: the Kennel, the Protestant Church of our Lady (as a gesture of reconciliation to his Protestant subjects who were upset because of his change of belief) and the Japanese Palace. Other castles, such as Hunting Lodge Moritzburg and Schloss Pillnitz were rebuilt and expanded. He also laid the foundations of the collections of today’s important museums such as the Picture Gallery, the Green Vault, the porcelain collection and others.

MAGNIFICENT BUILDINGS IN AND AROUND DRESDEN IN THE TIME OF AUGUST THE STRONG AND HIS SON AUGUST II

Not only his passion for buildings and collecting consolidated August’s legendary reputation, his costly and imaginative festivals and celebrations were also part of it – which often included elaborate costumes and corresponding decorations. His splendid celebrations, which he also celebrated in his second residence in Warsaw, helped him to regain the Polish crown, which he had to do without after losing battles against Sweden in 1706/07. The ‘voters’, the Polish nobles who celebrated festivals with him in Dresden and Warsaw, were so impressed that they offered him the lost crown again in 1709. (Is that true?) However, one thing did not succeed: his attempt to convert Poland into a monarchy that could be inherited and thus ‘automatically’ securing the Polish crown for his son after his death.

However, all of this activity cost a lot of money – new sources of income had to be found. When August heard of an apprentice pharmacist who could produce gold, he had him fetched and provided him with a laboratory. Unfortunately, making gold was not that easy, but Johann Friedrich Boettger, the apprentice’s name, invented something that was also very valuable – he was the first in Europe to manufacture porcelain, also known as ‘white gold’. The still world-famous Meissner porcelain was created in a manufactory in Meissen and was a new source of money – which, however, could not compensate for the enormous expenditure alone.

However, August had other ideas to cover his vast expenses, so he initiated a tax on consumption in 1703 – you can call him the inventor of VAT. The economy, which was quite prosperous due to existing trade and natural resources, was supported by the state and was, among other things, also export-oriented due to the Leipziger Trade Fair (which was already taking place at that time). In his reign, 26 factories were created, and in some of them, August himself operated as an entrepreneur, such as in the the Olbernhauer Armoury.

The monarch died at the age of 62 after a spell of weakness- it is known that he had diabetes, which at the time was not yet treatable. He was buried in the royal crypt in Krakow. At his request, his heart was kept in a silver capsule, which is located in the Dresden court church – the legend that his heart always starts to beat when a beautiful woman walks past is one of the many stories that are told about this famous Saxon ruler…

The son: Friedrich August II. (1996-1763)

For his son and successor, Friedrich August II., August the Strong had already arranged some things – he too had converted to the Catholic faith and was strategically married to the emperor’s daughter Maria Josepha (which strengthened the alliance between the Wettins and the Austrian Habsburgs).

With some Russian support, he was also elected King of Poland in 1733 and remained in this position for at least another 30 years. In the meantime, however, there were armed conflicts once more – Saxony was involved in the First (1740-42) and Second (1744/55) Silesian War – as the name suggests, it was a war fought for the Province of Silesia, which belonged to Austria, but was claimed by Prussia.

The Prussian army marched into Saxony in 1756, and the subsequent seven-year war was about power claims between Prussia and Austria. Austria had a lot more allies than Prussia, including Saxony, which led to its victory over Prussia. For Saxony, this war had fewer positive effects: the country was destroyed, almost 10% of the population died in the war and Saxony’s position in the European power structure also deteriorated. Prussia secured the contested Silesia, which could have become a territorial link between Saxony and Poland. In addition, Saxony was heavily in debt. Unfortunately, August the Strong’s son only inherited some of his father’s characteristics, including his desire for abundance, understanding of art and passion for collecting. During his reign, he acted irresponsibly and carelessly. He was irresponsible in that he transferred the government of Saxony to Count Heinrich of Bruehl (1700-1763) and irresponsible because he transferred the government businesses of the state of Saxony to Count Heinrich von Bruehl (1700-1763).

The last name is still known today through the ‘Bruehlsche Terrasse’ (which translates to ‘Bruehl’s Terrace’) in Dresden, a terrace which the count extended with various building ensembles.

Otherwise, Count Heinrich of Bruehl was attributed characteristics such as a tremendous addiction to waste, bribery and intrigue, combined with the inactivity – or inability – to prepare his country for the foreseeable military conflict. He was probably only a skilled diplomat and organiser.

When both returned to their battered country after the war, they died in quick succession in the fall of 1763 – the main culprits in the plight.

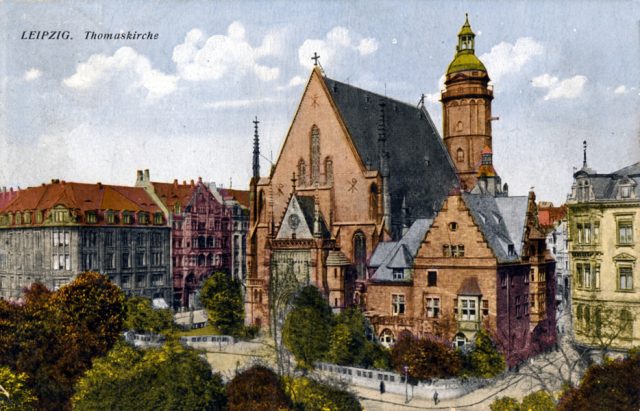

If Dresden was a centre of courtly culture, Leipzig as a counterpoint was a centre of bourgeois intellectual life. An urban culture developed in the fair and trade metropolis from the beginning of the 18th century. Of course, it was still shaped by courtly traditions and role models. For example, wealthy merchants commissioned magnificent residential and commercial buildings – some like the Gohliser Castle even had palace-like dimensions. It also became a centre for literature and theatre. An intellectual sociability developed in coffee houses, reading circles and literary associations. It was certainly no coincidence that the book trade and publishing industry in Leipzig was already well developed in the 18th century. How Leipzig developed into the most important publishing town in the world in the 19th century is further described in this article, which is unfortunately only available in German for now.

Friedrich Christian (1722-1763), a reformer,

who had been a critic of Count Bruehl and his father during his lifetime. Handicapped from birth and assigned to a wheelchair, he had not been put off by his mother, who had urged him to give up the throne in favour of his younger brothers. With fellow campaigners who were closer to the bourgeoisie, he initiated long-planned reforms to streamline the court, to standardise administration and to implement austerity measures. Unfortunately, his term was very short – he passed away after only 74 days in office.

However, his wife Maria Antonia of Bavaria (1724-1780) continued his reforms, together with her brother-in-law Prince Xaver (1730-1806) as regent for Elector Friedrich Albert III, who was not yet an adult. (1750-1827).

Maria Antonia was very talented musically – she composed operas and performed as a singer and harpsichordist. During her lifetime, she had supported her husband’s reform efforts. She was also active as an entrepreneur – she owned a cotton factory and acquired the Bavarian brewery in Dresden in 1763 – and so Bavarian customs of her home extended to Saxony ?.

She had a disagreement with her brother-in-law in 1765 over the question of the future Polish king. While Prince Xaver renounced his claim to the throne, she, as the mother of the heir to the throne, wanted to hold on to it at all costs. In the end, Prince Xavier was able to push through his decision to renounce the throne.

Elector Friedrick August III / King Friedrick August the 1st (‘The Just’) (1750-1827)

His foreign policy was initially characterized by balance and neutrality.

Even the economy within the country was revived after all the waste and war. Manufactories were subsidized by the state – by the turn of the century, this had resulted in more than 150 start-ups. Particularly many new companies settled in the foothills of the Ore Mountains between Freiberg, Chemnitz, Zwickau and Plauen. In addition to luxury items such as porcelain, musical instruments and weapons, textile products were also produced. The first factories were built in the transition to the 19th century, such as the machine-operated cotton spinning mills in Chemnitz. In this first phase of the industrial revolution, Saxony played a pioneering role alongside the Rhineland and Silesia.

However, when the French Revolution began, war started once again in 1793 (First Coalition War). The monarchies, including Saxony with a contingent of almost 10,000 soldiers, fought against France.

In the famous battle near Jena and Auerstedt in 1806, 20,000 Saxon soldiers fought on the side of Prussia against Napoleon and his troops. The devastating defeat of the Prussian side initially had an impact on Saxony as well: it had to pay high maintenance payments for the French occupation forces. However, in 1806, winner Napoleon granted the inferior Saxons more favourable conditions with the ‘Peace of Poznan’, naturally not without asking for something in return: Friedrick August III. had to become a French ally and join the Rhine Confederation, as well as promise up to 20,000 Saxon soldiers for the continued warfare that the ruler wanted to pursue. For all of this he was elevated to first Saxon king and received the district of Cottbus as compensation for lost land in the Erfurt area. It had long been clear that Prussia and Saxony were not really friends. With the regulations dictated by Napoleon in the ‘Tilsiter Peace in 1807, Saxony received the territories of Poland, the so-called ‘Duchy of Warsaw’, which had been conquered by Prussia. So, once again, parts of Poland were ruled by a Saxon king. Not for long though; Prussia revenged itself.

The first Saxon king remained an ally of France until France’s demise after the bloody three-day battle of nations near Leipzig in 1813. During the battle, Saxon soldiers mostly overran their opponents. But that didn’t change the consequences:

King Friedrich August I was arrested by the opponents as a prisoner of war, the country was now ruled by a government under Russian and later Prussian leadership based in Leipzig. As the only regent of his state, he could not be present at the negotiations at the Congress of Vienna, at which the territorial reorganization of Europe was negotiated.

The spoils of war in Saxony were hotly debated there – of course there were different interests among the winners, and everybody put theirs over the that of the others. In the end, a compromise was reached: Saxony lost its shares of Poland (which Russia gained) and had to give up even more territory: the northern parts of the country with Wittenberg, Cottbus, Weissenfels and Torgau, the entire Lower Lusatia and significant parts of Upper Lusatia – these parts went to the Prussian rival. This gave Prussia over half of the area of former Saxony and 40% of its inhabitants – so far this had been about 2 million people.

In the political structure of the German Confederation, Saxony was only a third-ranking force. The first Saxon king was popular among his subjects – and surprisingly remained so even after his defeats. On his return, he was greeted enthusiastically. He was credited for his honesty, as well as being seen as a moral authority AND as just – he was given this nickname during his lifetime. After these turbulent times, he pursued a very conservative and restorative policy of preservation in his last decade and the country’s population increased again and continued to prosper economically.

When King Friedrich August I died in 1827, his younger brother succeeded him – he himself had a daughter, who remained unmarried for the rest of his life. Brother Anton was over seventy when he took the throne and was not very popular in his rather short term. Criticism arose because he too seemed to have no intention of introducing reforms and more liberal politics. Overall, however, this was balanced out with two things he did that helped the country: he dismissed the very conservative former State Secretary Graf Einsiedel, who opposed reform, and appointed the popular Prince Friedrich August II in 1830 as a co-regent.

Friedrich August II (1797-1854)

had initiated reforms in the Saxon state during the lifetime of his co-governing uncle, that included a constitution and the ability for citizens to co-determination more. ‘People’ are relative here – it meant only wealthy citizens, but that was already a step forward at the time. A kind of constitutional monarchy was created, similar to that of Baden and Württemberg.

In the new constitution of 1831, the powers of the king were laid down, which were far-reaching enough: the king was the sole bearer of state power, he was able to appoint and dismiss ministers, to introduce bills and also to advertise new elections. However, the Saxon rulers, even the future ones, never really overexerted these powers. There was a people’s representation, called the second chamber as well as a first chamber, consisting of representatives of the nobility, the church, the larger cities and the University of Leipzig. These members were appointed by the king or were delegated by the respective institutions.

In addition, the Saxon State Ministry was formed with 6 departments, whose ministers were of equal rank. There was no prime minister. In comparison to other countries, Saxony was not exactly a pioneer when it came to this (the Grand Duchy of Baden had already introduced such a structure in 1818), but they were also not too late, in contrast to Oldenburg for instance.

The renewal was rounded off by various other social laws. In the Saxon School Act of 1836, the compulsory school attendance of children aged 6 to 14 years was laid down. The communities were obliged to build a school building, maintain it and pay the teachers their wages. During this time, the children were not allowed to start an apprenticeship, so compulsory schooling was also an effective means against child labour.

Something was also done for the poor: the municipalities were obliged to build public facilities for the poor and the first state orphanages were also built. Furthermore, other disadvantages that citizens suffered from were reduced: children born out of wedlock were legalised from 1831 onwards and from 1838 women were legally independent in court. Last but not least, a tax law abolished privileges for the nobility, and new city (1832) and municipal rules and regulations (1839) allowed these to self-government.

The situation regarding agriculture was also reformed: Frontier peasant services were abolished, including the century-old obligation to pay inheritance interest to the landlord for the tenants. After paying a compensation sum (for which cheap loans could be obtained), the land was transferred to the farmers free of debt. In addition, the purchase and sale of knightly estates and farms was simplified and the previously existing duty of the farmers’ children to act as servants was abolished. This list makes it clear which medieval laws and customs had still existed up to then!

These reforms brought agriculture to new heights.

Incidentally, it was the unpopular Prussian neighbour that was a model for all of these reforms. Even if it is difficult to admit … Reforms had already been implemented there earlier.

In terms of trade policy, the decision was made to join the German customs union in 1834. Without membership, customs duties were due even within the German states and market access for domestic products to other landlocked countries was equally difficult.

Despite all the reforms, there was also a March Revolution in Saxony in 1848/49, since naturally there was still a lot of misery in the country, experienced by the poor urban proletariat which was created by the growing industrialization or experienced by those living in the countryside. However, the riots initially turned out to be rather unspectacular, especially since King Friedrich August II soon fulfilled the main demands that were expressed: the freedom of the press, a more liberal president for the Chamber of Deputies, as well as general assembly, association rights and the introduction of general and equal voting rights.

Unsurprisingly, the democratic left won an overwhelming victory in the subsequent elections. Their centre was in Leipzig, where their main leader Robert Blum (1807-1848) came from.

When the king dissolved the state parliament in 1849 due to a dispute over the recognition of the Paulskirchen constitution in Frankfurt, there was an uprising of more radical forces called the ‘Dresden May Uprising’. After street fights, the uprising was brought to a standstill with the help of Prussian troops and the leaders were persecuted and sentenced, although the death sentences that had been passed were probably never carried out. As in other countries, this was followed once again by a step backwards: by means of a coup d’état, almost all of the achievements of the March Revolution were lost! In the following years, the government pursued a rather traditional policy with more surveillance. For instance, the political attitudes of primary school teachers were monitored by the state.

August Friedrich II’s life ended abruptly with a fatal accident. In the summer he went to Bavaria with his second wife to visit their noble relatives. He continued to Tyrol, an area he had visited numerous times, as he was fascinated by the mountains. On a steep driveway, his touring car skidded and he was thrown out of the carriage between the horses. A horse kicked him on the head. While he was quickly brought to the next inn, he never regained consciousness and died. As if travelling was less dangerous in the past!

His brother Johann (1801-1873)

continued his politics as his successor – like August Friedrich II. he was also a fine spirit who, as a patron, not only committed to promoting music and opera, but also science and scholarship. As far as the preservation and restoration of traditional art treasures was concerned (many of which could already be admired in the already existing museums), he was a pioneer in the preservation of monuments.

Johann was also an author himself, and his translation of Dante Alighieri’s book Divina Commedia under the pseudonym ‘Philates’ was recognized by scholars. His influence strengthened Dresden’s reputation as a centre of German culture and intellectual life.

Politically, the Habsburgs were approached again in the following years. A free trade agreement between Prussia and France was signed in 1862. Anything else would have been stupid and detrimental to the economy.

In the Prussian-Austrian war in 1866, however, 32,000 Saxon soldiers fought alongside the Austrians under the command of the future King Albert. And lost once more!

As a result, they joined the North German Confederation, which was dominated by the Prussians and had to grind their teeth to accept some restrictions regarding their rights as a sovereign state. But at least it was able to remain an independent state! Otto von Bismarck had argued for this with King Wilhelm I of Prussia. As a strategist, he certainly did not do that without a motive: He would later have a loyal advocate for the idea of the German Empire at his side.

In the subsequent war against France in 1870/71, Saxony fought side by side with the Prussians. Crown Prince Albert proved to be a skilful general and, with the troops he led, played a decisive role in the victory in the Battle of Sedan, which led to the capitulation of the French army. This secured him recognition and popularity throughout Germany – even in Prussia.

Negotiations on the inclusion of the southern German states into the German Empire were also successfully concluded under the leadership of the Saxon Foreign Minister Freiherr of Friesen, together with Berlin diplomats. At the proclamation of the German Empire in Versailles, the incumbent King Johann was represented by his two sons Albert and Georg, both later Saxon kings. Was it a coincidence that another sovereign was missing? Heinrich XIV, the last ruler of the small principality ‘Reuss older line’, whose story is told in this article, had indeed approved of the Imperial Treaty, but rather with reservations, as he reported to his confidant King Johann. Henry XIV felt that Prussia had become too powerful through the founding of the empire; he favoured the continuation of the previously existing federalist structures.

Saxony, however, actively supported the newly founded German Empire in the following years and also readjusted its internal administration. In 1873, administrative reforms separated the local judiciary and administration. With a new law regarding schooling, schools were placed under state supervision – previously this had been in the hands of the church. Hence, there was a separation of church and state. King Johann died in the same year. His eldest son

Albert (1828-1902),

the successful general, became king of Saxony. He continued to align his country with the German Reich and pursued a policy that supported compliance with the federal order and aimed at reconciliation with the powerful Prussian neighbour. His wife Carola would be the last Saxon queen. The two had married in 1853, most likely out of love, which was not common at the time. Carola had a ‘good name’ but was rather poor in financial terms. For this purpose, she converted to the Catholic faith shortly before Prince Albert met. However, none of this was an obstacle for Albert to marry her. The marriage, which lasted 49 years, was considered happy. She remained childless.

Carola engaged in charitable activity in a variety of ways. As a crown princess, she founded the Albert Association (named after her husband) for the training of nurses – this gave rise to the interdenominational sister community of the Albertine women. She founded various associations, which were devoted to the support of needy widows and orphans, the care of children (to support working parents), the retirement of servants and the establishment of pulmonary care facilities, among other things. She also took care of the promotion of the professional activity of women by acquiring a sewing machine association and by establishing a technical and trade school for women in Leipzig. She also had an educational institution built for physically handicapped children (then called cripples).

It was not uncommon at the time that so called ‘mothers of the country’ were involved in charitable work; Louise von Baden was too, as has been recounted in this article about the Grand Duchy of Baden.

Without wanting to diminish the importance of this charitable work, it was the only way for the rulers’ wives, as well as noble women, to engage in meaningful activities and also to gain recognition. After all, this was a time when the professional or occupational training and education of women was only beginning to develop and pursuing a profession would not have been possible for these women at that time anyways. The tradition for the wives of rulers (today people would call them the heads of the government) to be socially committed has survived to this day. The wives of our Federal Presidents also support charitable associations and organisations and campaign for certain issues that would otherwise not find the attention they deserve in society. A good tradition, in my opinion.

Back to Saxony in the Empire and its traffic policy. Saxony wanted to make its own decisions instead of being subjugated to Prussia, such as on the railway issue. Bismarck wanted to take over all of the country’s rail networks for a unified rail network. Saxony was opposed to this and hence transferred the mostly privately-operated local railways to Saxon state ownership in 1873 and the following years.

Other countries such as Württemberg and Bavaria also resisted the unification of the rail networks and kept their tracks in their own hands. The idea of a uniform railway for the German Empire failed – it would only be implemented after the First World War. However, the Prussian state railways were quite dominant simply due to the size of the state, and in the course of the imperial period they also took over various routes outside their territory or merged with the Hessian state railways in 1897. Saxony had the densest rail network in all of Germany, which of course was very beneficial for its economy.

Politically, the Social Democratic party was also popular in Saxony; no surprise, since Saxony was one of the industrial centres of the country with a growing number of workers who wanted to have their interests represented in the country. The social democratic party won 32.5 percent of the vote in the state elections in 1895. In order to prevent the Social Democrats from becoming even more powerful, the conservative-liberal majority in the state parliament decided to do something about it: they changed the (until then) quite progressive voting right to a three-class voting right, which was only changed again in 1909 despite numerous protests. This article explores the right to vote in Saxony (for now unfortunately only in German available) and recounts the individual developments in more detail.

After Albert’s death in 1902, his brother Georg (1832-1904) initially took his places as king. However, this move made him extremely unpopular in his short term of two years, since he had not renounced the throne in favour of his son Friedrich August. In 1904 he died of the flu and then his son followed him:

Friedrich August III. (1865-1932)

as the last king of Saxony. He is remembered by his down-to-earth nature as a bourgeois king and also by his numerous sayings, which were told in a Saxon dialect. Kaiser Wilhelm II’s judgement of him, that he was more ‘August’ than Friedrich was unjust, since he was a pragmatic and popular ruler.

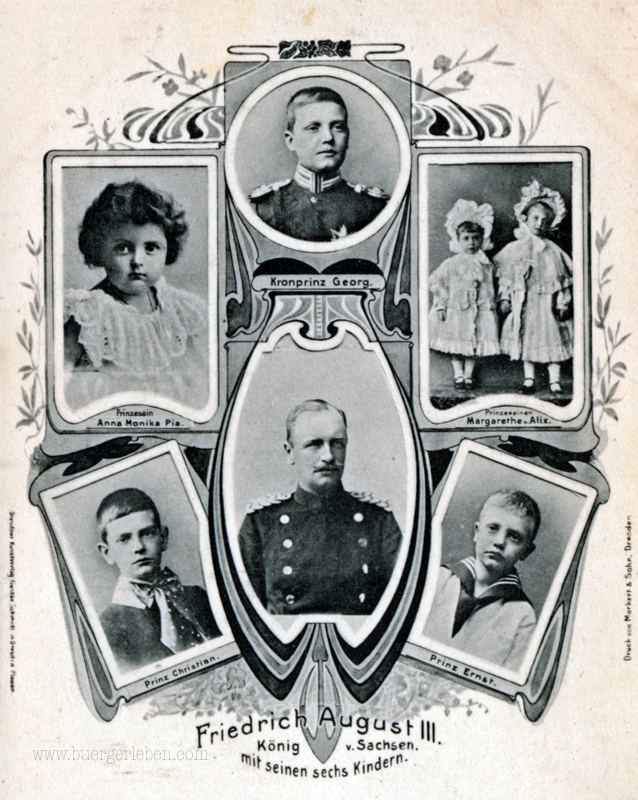

Friedrich August III had been married to the Archduchess Louise of Austria-Tuscany. The marriage was initially a happy one and the couple had six children. While the princess was popular with the people, she had difficulties with the strict court etiquette and was not averse to flirting with others. In her defence, there were powerful personalities at the court which were not well inclined towards her: her father-in-law (who would later be King George for a short-term) thought her too popular and the relationship with his sister Mathilde of Saxony, who also lived at the court, was difficult. Louise was probably exposed to all kinds of intrigue. Whether it was a lover (as the public was told at the time) or her unhappy life at the court that made her want to leave is unclear, but she left in 1902, pregnant with her seventh child, fleeing from the Dresden court to Geneva, where she met her brother and her lover. Louise could not be persuaded to return. Without asking her husband Friedrich August, King Georg ordered for the couple to divorce in 1903. The princess did not claim anything, although she she kept her youngest child Anna Monika Pia initially, later (from 1908 onwards) the little one grew up with her father, the Saxon king (there was a paternity test). Of course, the whole thing was a huge scandal at the time, which was reported in all the newspapers.

Louise enjoyed her life with other lovers and lived in different places, in France, at Lake Constance, Mallorca and in Brussels. The Viennese court had also rejected her.

After she stopped receiving payments at the beginning of World War II, she was suddenly penniless. She died, impoverished and selling flowers, in Brussels in 1947.

Pictures from happy family days: Portrait of the princess, with 4 of her 6 children, visit of the king of the youngest daughter (who first lived with her mother, later also with her father)

And so the king became a single father of five or six children (one child died at birth). He was also a supporter of the fine arts: he spent a third of his private income on promoting art and culture. This benefited the museums and collections, but also the concert and theatre scene. The Royal Playhouse and the Semper Opera House had a good reputation and the popular composer, Richard Strauss, came to Dresden for the premieres of his operas Salome (1905), Elektra (1909) and Der Rosenkavalier (1911).

The country continued to prosper economically as one of Germany’s industrial centres. Until World War I came. Saxon soldiers also went to war, a total of about 750,000 by the end of the war in 1918. Almost half of them were wounded, 210,000 died and 19,000 soldiers went missing. The mood in the country was similar to that in all of Germany. The initial enthusiasm for the war quickly gave way to disillusionment. Many smaller companies had to close, not only because there was no longer any business, but also because the necessary workers were often moved to industries that were critical for the war. In Saxony’s agriculture, the damage was not too bad – women replaced the missing men as workers.

The end of the First World War also meant the end of the Kingdom of Saxony. There were public demonstrations against the war and the poor provision of essential supplies in the larger cities of the country at the end of October 1918; at first, these protests were not explicitly directed against the ruling king and the monarchy. However, soon the widespread anti-monarchy sentiments also took hold of Saxony – revolutionary workers and soldier councils occupied public offices and buildings, and in Dresden the red flag was raised on the tower of the Residential Palace on the 9th of November 1918, declaring the monarchy abolished. The king left the city and declared his abdication of the throne on the 13th of November – at first only for himself (and not for his descendants, even though none of whom showed any ambition to rule). Hardly any blood was shed, as the king had forbidden the use of force against the mutineers.

The fact that many Saxons loved their king after his abdication (some despite it and others continued to) was already expressed in the 1920s when he came for a ‘visit’. Here is a (true) anecdote of the many that exist about him:

When passing through Saxony, the ex-king avoided doing anything that would reveal his presence. But his presence could not be concealed, and loyal Saxons gathered. At first the crowd behaved with restraint. Then cheers began, and when Friedrich August did not appear at the coupé window, the enthusiastic crowd drummed on the windows of the car. Then a window came down, a fist threatened the admirers and a familiar voice shouted: ‘Ihr seid mir scheene Rebbubligahnr!’ (In English, this roughly translates to : ‘You are beautiful republicans to me’)

When he died quite unexpectedly in 1932 at the age of 67, hundreds of thousands lined the streets at his funeral in Dresden to give him his last escort. He is buried in the Hofkirche. The line of the Wettin rulers of the Albertine line ended with him.

He is missing as the last ruler in the procession of princes mentioned at the beginning – with his consent, it was decided that the historic picture would not be altered. However, the Princely procession not only shows the Wettin rulers, but also representatives of the common people such as farmers, miners, pupils and students, artists, scholars and scientists, as a symbol of the bond between the people and the rulers.

As we have seen, there was a whole range of ruler-personalities, from the clever strategist to the ruthless despot. Correspondingly, the people’s connection with these rulers varied, but the connection was especially present with the last kings. The time of the monarchies had, however, also expired in Saxony after the First World War.

Besides my own research, articles and pictures from contemporary books and magazines about the Saxon Kingdom, the main source for this article was the book by Prof. Frank-Lothar Kroll “Geschichte Sachsens”, to whom I would like to express my sincere thanks for his support.

He has also published the following on the subject of Saxony: “The Rulers of Saxony: Margraves, Electors, Kings 1089-1918″ as well as: “Two States – One Crown. The Polish-Saxon Union 1697-1763″ with Hendrik Thoss.

Frank Lothar Kroll is Professor of 19th and 20th century European history at the Chemnitz University of Technology. He has not only described the history of Saxony in his books – he also frequently contributes to reports as an expert on the history of Saxony, for instance in the ZDF-History series Saxony’s Rulers (language German).

I would like to thank the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden for their support with photographic material.