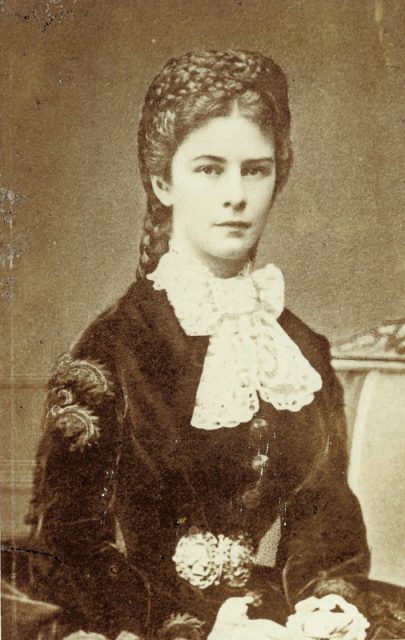

7 secrets of Empress Sisi, you probably didn’t know

A guest post by Petra Herzberg

Secret No. 1: A tattoo on her shoulder to represent her love for the sea?

Empress Elisabeth loved the sea. She loved it so much that on her crossings to Corfu or Madeira she had herself tied to a mast, sitting on a chair and enjoying the waves washing the cold salt water over her body with full force. If it was too cold, she made use of a glassed-in pavilion that was exclusively at her disposal. All the sailors and ladies-in-waiting around her were seasick, but Sisi never was. On the contrary, the more the ship rocked and struggled through the waves, the freer she felt. The seawater washed away her worries and cares.

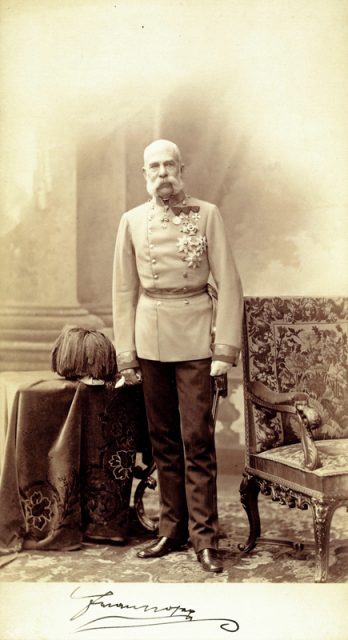

Does is come to any surprise then, that in later years she had a small anchor tattooed on her left shoulder as a sign of her attachment to the sea? Her lady-in-waiting Irma Gräfin Sztaray, who accompanied her on her travels, reported that Sisi got the tattoo in 1888 at the age of 51 in an infamous harbour bar. Sisi’s husband, Emperor Franz Joseph I, knew nothing about it. When he found out, he was stunned once again, because his wife kept surprising him with quite strange views, actions and desires. He remembered her once wishing for a fully furnished psychiatric ward, a young royal tiger or a medallion for her birthday, already knowing that she would receive the medallion.

Secret No. 2: The song of the yellow domino – an empress on the wrong track

During the carnival and ball season of 1874, the bored empress managed to escape unseen from her hated Hofburg. Sisi, disguised as a yellow domino, with a wig, veil and mask, was accompanied by her lady-in-waiting, Ida Ferenczy, dressed up as a red domino. The destination was a ball at the Vienna Musikverein.

The emperor was traveling and, moreover, she was forbidden to enjoy herself as she pleased. Out of boredom and defiance, she let Ida in on her plans and the ladies drove up to the music society undetected. There she noticed the dashing-looking Friedrich (Fritz) Pacher List zu Theinburg, a ministerial official, whom she boldly spoke to through Ida, who called herself “Henriette” that evening. He followed the red domino into the empress’s box, who pretended to be “Gabriele”. The two quickly began a conversation and talked for quite a while. Sisi asked him what people in Vienna were saying about the empress, the emperor and the court and was amused by his answers. Elisabeth wrote down his address and promised to write to him. The young man was curious and wanted to know who was really hiding behind the mask, surely already having guessed. Elisabeth’s, or “Gabriele’s” discomfort in the crowd, overly slender figure, elegant gait and the aura that surrounded her even in her costume aroused in him a suspicion: Was this really the empress Elisabeth of Austria, who held out her delicate gloved hand to him and let him lead her through the Golden Hall by the arm, as light as a feather? He had to find out! He lifted her veil, which she wore over her face, but she was quicker and batted his hand away with her delicate silk fan. Suddenly, Ida was between them, urging her “friend” to leave with her. Fritz managed to take the fan from Sisi. “You are not Gabriele, your name is Elisabeth and you are 36 years old,” he whispered to her before she escaped from him in horror and grabbed Ida’s arm, running through the crowd to their carriage.

Later, as an ancient man, Fritz showed the fan to the empress’s first biographer, Egon Count Conte Corti, along with some letters, when the latter sought him out to do research for his biography of the empress. Conte Corti recognised Elisabeth’s handwriting and the delicate fan, which was already falling apart. Conte Corti got on Fritz’s trail because he had learned from Ida that for many years after the ball there had been an exchange of letters between Fritz and Elisabeth – alias “Gabriele”. The empress sent Fritz letters from Munich, London, and even from Rio de Janeiro, amongst other places, adding only the address of a postbox, rather than her own. Fritz wrote back, but only a few letters actually reached the empress, the rest were never picked up and never read. At first, Elisabeth enjoyed confusing and misleading Fritz, but his increasingly specific questions and finally rather rude lines about her true identity caused Elisabeth’s interest to fade.

She ended the adventure with a simultaneously mocking and melancholic poem, which has been preserved and is entitled “The Song of the Yellow Domino – Long Long Ago”. Fritz would not forgot the beautiful woman and the glittering ball night for the rest of his life and kept her fan and letters until his death on May 12, 1934. He lived to be 87 years old and died knowing that it was the Empress Elisabeth of Austria whose arm he held at the 1874 carnival.

Secret No. 3: Corfu retreat – skinny dipping

Elisabeth came to Corfu for the first time in 1861 for a spa stay and fell in love with the beautiful Greek island. She had a castle built there, which she named “Achilleion”, dedicated to her idol Achill. On her escapes from the Viennese court, she learned Greek and took long walks and rides in the olive groves. She liked to enter unannounced in the kitchen of the small farmhouses, looking around curiously and asking the puzzled peasant women for a glass of milk. Often she was driven away with rude words, but when she was recognised, the joy of the farmers was great.

Elisabeth was a good swimmer and loved bathing in the sea. From the beach to the water, cloths were hung to the right and left of the path so that she could slide into the sea unseen. Naked and with open hair, she would swim through the waves like a mermaid.

With her Greek valet Constantin Christomanos, she wandered at high speed in sweltering heat, reciting Shakespeare and translating texts from modern to ancient Greek and vice versa. She spoke German, English, French, Hungarian, ancient and modern Greek, Bohemian and Croatian, and loved to keep those around her in the dark about what she was discussing – mostly in Hungarian with her Hungarian ladies-in-waiting. This particularly annoyed her mother-in-law, who deeply hated anything Hungarian. After all, it was a Hungarian who had- unsuccessfully – attempted to assassinate her son Franz Joseph in 1853.

After Elisabeth’s death in 1898, the Achilleion was first bequeathed to her elder daughter Gisela, who was not interested in it, and then sold to Kaiser Wilhelm II, who enjoyed staying at the resort. After his death, the villa began to fall apart, and was soon turned into a casino by the Greeks. It was only renovated much later, when the Greek government became aware of its value. To this day, there are attempts at auctions to buy back original furniture and restore the villa to how it looked in Sisi’s day. Presently, visitors of the castle can see the study of Kaiser Wilhelm II with the famous chair in the shape of his riding saddle. There are also many pictures, statues and photos of Sisi that visitors can admire.

Secret No.4: Katharina Schratt -Sisi’s unofficial deputy?

It is generally known that Emperor Franz Joseph had some extramarital affairs, which was quite common at the time. In 1886, the young actress Katharina Schratt enjoyed great success at the Hofburg Theater in Vienna. The fresh and sweet Viennese girl aroused the interest of the emperor. Sisi noticed this, sent for Kathi and established a friendship between Franz Joseph and her. She gave Franz Joseph a painting of the actress and from then on, Kathi became a “friend” of the imperial couple.

Elisabeth was aware that this constellation gave her freedom, putting the emperor in good company and allowing her to travel without a guilty conscience. Katharina received many gifts from the emperor, including jewellery and even a villa. The villa was within walking distance of Schoenbrunn Palace, so the emperor was able to visit her in the morning for breakfast. Katharina entertained him with homemade guglhupf (a typical cake traditionally baked in a circular Bundt mold) and the latest Viennese gossip. It was clear that the two of them started an affair, which can be deducted from letters which read “Please receive me in bed”. Sisi even agreed to Franz Joseph marrying again in the case of her death – but only if it were to be Katharina Schratt to take her place. After Sisi’s death, there is even said to have been a secret wedding between the two lovers, but this was never proven.

Secret No. 5: Sisi’s denture – an observation by Romy Schneider’s grandmother.

All her life Sisi had bad teeth, which were also quite yellow. She was ashamed of them and therefore did not smile in photos. She also spoke very softly and often held her hand in front of her mouth. Only later did she find a good dentist who made her a denture. In 1898, Rosa Albach-Retty, Romy Schneider’s paternal grandmother, once observed two ladies in a country inn in Bad Ischl. She did not recognise them immediately. When the second lady, Sisi’s lady-in-waiting, briefly left the table at which they were sitting, Rosa observed that the lady who remained behind suddenly took out her denture in a flash, held it sideways over the table and rinsed it with water. Then she pushed it back into her mouth with incredible elegance. Rosa was so impressed by this that she later mentioned this experience in her memoirs “So Short Are a Hundred Years”.

Secret No. 6: The hairdresser as a doppelgänger

Sisi’s hair is legendary. It was chestnut-coloured, slightly wavy, heavy, and reached the back of her knees. The pretty Viennese Fanny Angerer was hired as Sisi’s personal hairdresser when Sisi saw the elaborate hairstyles that Fanny had created for the actresses at the Hofburg Theater. Fanny was in charge of Sisi’s hair, which needed to be taken care of for three hours every day. In addition, the hair was washed with egg and cognac every three weeks, and a whole day passed before it was dry again. On those days, the empress was not available to anyone.

Fanny played a central role when it came to Sisi’s appointments: If Sisi’s hair was well done, she went to her engagements, such as receptions and balls, but when it wasn’t, or when Fanny was ill and the substitute couldn’t manage to replicate the famous pin-up hairstyle that Fanny created especially for the empress, Sisi canceled all her appointments. Fanny became so important that her husband was appointed court secretary, allowing Fanny to continue to offer her services to the empress.

In Sisi’s time, only unmarried women were allowed to work in the court. From then on, Fanny’s name was no longer Angerer, but Fanny Feifalik. She was tall, very pretty, slim, and resembled Sisi from afar. When Sisi didn’t feel like fulfilling her royal obligations, she would often send Fanny in her place. She would even send Fanny ahead swimming and choose to swim in a different part of the lake or the sea to mislead onlookers. Fanny became so used to Sisi’s ways that she developed certain tricks to appease the empress. For instance, Sisi hated having her hair combed out and would scold Fanny if hair was found in the comb after its daily brushing. To pacify her, Fanny simply stuck a piece of adhesive tape under her apron, where she made the combed-out hair disappear in a flash, allowing her to present an empty comb and have her peace.

Secret No. 7: Sisi’s vice

In the late 19th century, morphine and cocaine were common painkillers that were considered harmless. They were often prescribed thoughtlessly by doctors for painful conditions and psychological complaints. Many users even owned their own syringes, including Sisi. Her cocaine syringe can be seen in the Sisi Museum in Vienna.

Sisi liked to feel free by smoking cigarettes. When she drove through Vienna smoking in an open carriage, she enjoyed the murmurs of onlookers this would cause. She loved to shock her hated entourage at the Viennese court. Since she was also constantly on a diet (at a height of 1.72, she never weighed more than 50 kg throughout her life), smoking helped her suppress the feeling of hunger.

She loved to be different: she was the rebellious empress, the poet empress, the athletic empress, the self-confident empress, the empress who made decisions for herself, defying the court etiquette. And above all, she knew that she was upsetting her hated mother-in-law with her behaviour.

This repeatedly led to conflicts with her husband, who was caught between the two women, his mother whom he wanted to honour and his wife whom he adored. Often he did not know how to act. Most of the time he decided in favour of his mother, leaving behind a disappointed wife who was withdrawing more and more from him. He only sighed when the bills came for the many trips and horses she consoled herself with. He paid – and then sighed again.

When he learned of her death in Geneva on September 10, 1898, he said to his adjutant general, Count Paar, who delivered the terrible news, “You do not know how I loved this woman.” Elisabeth was fatally wounded by the Italian anarchist Luigi Lucceni, who stabbed her in the heart with a homemade file.

Lucceni had originally wanted to kill the Duke of Orleans, but the latter had canceled his trip at short notice. Lucceni learned from a newspaper that the Empress of Austria was staying at the Hotel Beau Rivage under the incognito name of “Countess of Hohenembs” and waited for her there. He explained his act by saying that “whoever does not work should not eat.” He hated the aristocracy and wanted to be remembered with the assassination. However, he broke down mentally in prison and hung himself with his belt in his cell eleven years after the crime in 1910. He left behind his written memorials, which can still be bought in stores today.

About the author

Petra Herzberg’s passion is Sisi. She knows everything about the famous empress of the K & K monarchy. Everything? Yes, EVERYTHING you can get hold of! Not only has she read all the (German) books that exist about the life of Sisi and her husband Emperor Franz Joseph, she also collects pictures, photos and figurines of Sisi.

Visiting Petra Herzberg in her home, I admired her collection and asked her

when her enthusiasm for Empress Sisi began. She told me that she discovered the first book about Sisi, the biography by Brigitte Hamann “Kaiserin wider Willen” in 1981 (?) at her grandmother’s and devoured it. After that, she was hooked, and read more about the life of the fascinating Sisi. She began to collect the books and travelled extensively to the many places the empress had lived, from her beloved Vienna, which she visits regularly, to Budapest or even Corfu. Until now, she has pursued this passion in her free time. Professionally, she has been successfully working in the banking industry for many years. A second passion which she shares with Empress Sisi, this one more by chance, is horseback riding, preferably in a side-saddle, which is her compensation from city life on weekends. And when there is still time left, you can find her working on her book. Guess whom it’s about…

When I asked her about what she thinks about the many “Sissi” movies that are broadcast every year, especially around Christmas, she comments “There is some truth to them, but the sugarcoated truth doesn’t taste quite so bitter”. And even though they often don’t reflect reality, she says in a conciliatory way that the movies are connected to childhood memories for her and therefore are still “must-sees” at Christmas!

In a series by RTL, Sisi’s story was filmed again. Here are a few visual impressions of it:

ALL THREE IMAGES COPYRIGHT RTL

The episodes can be streamed on RTL+.

A little hint on of the different spelling: Sisi was historically spelled with one ‘s’.

If you want to read more articles about Sisi, the following have been published in german by Petra Herzberg: “Sisis Reisen – Flucht oder Abenteuer?“; “Sisi und der Reitsport vor 150 Jahren“.

Christian Sepp has published these german articles on Sisi’s little sister: “Sophie Charlotte – das dramatische Schicksal…” on Sisi’s mother Ludovika and her family.

Regarding King Ludwig II and his struggle for friendship and relationship (including with Sisi), there is another german articel by Marcus Spangenberg.